8

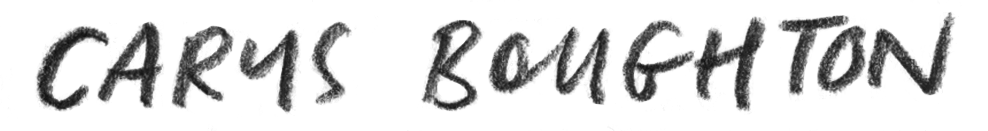

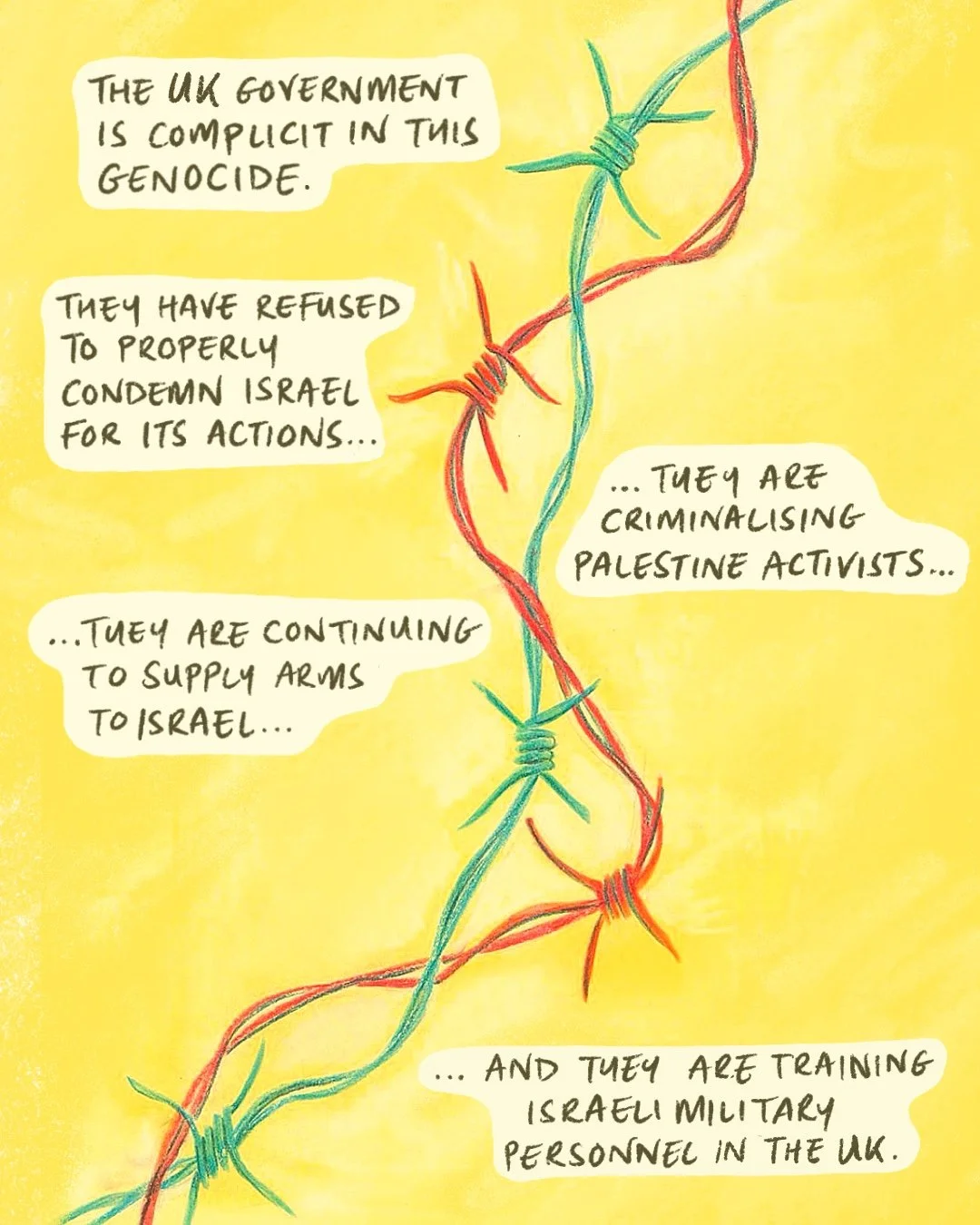

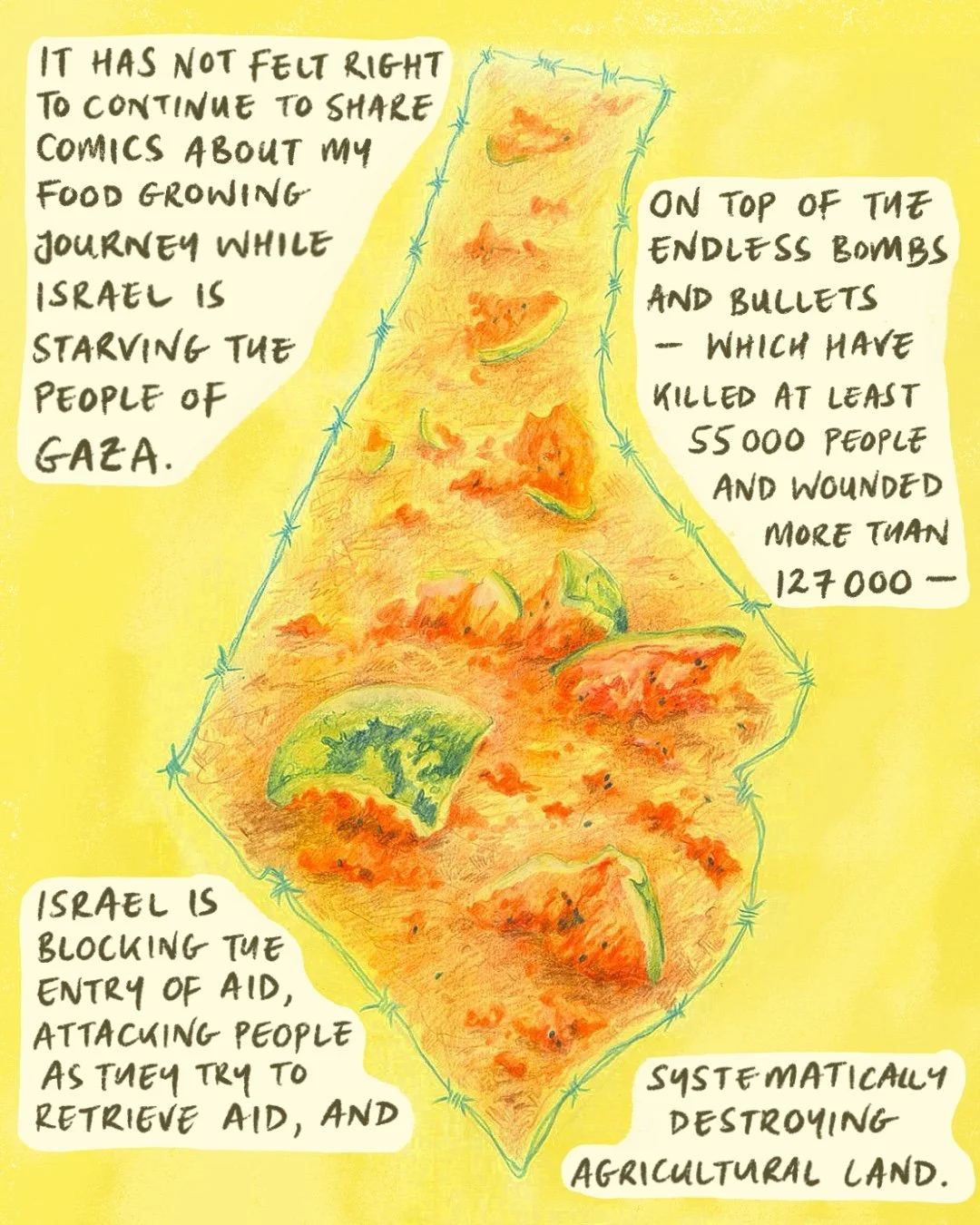

The people of Gaza are being starved: what can we do? June 2025

1

Arbroath and Auchmithie Fishing Tales, summer 2024 (1/5)

1

Overfishing? Arbroath and Auchmithie Fishing Tales, summer 2024 (2/5)

1

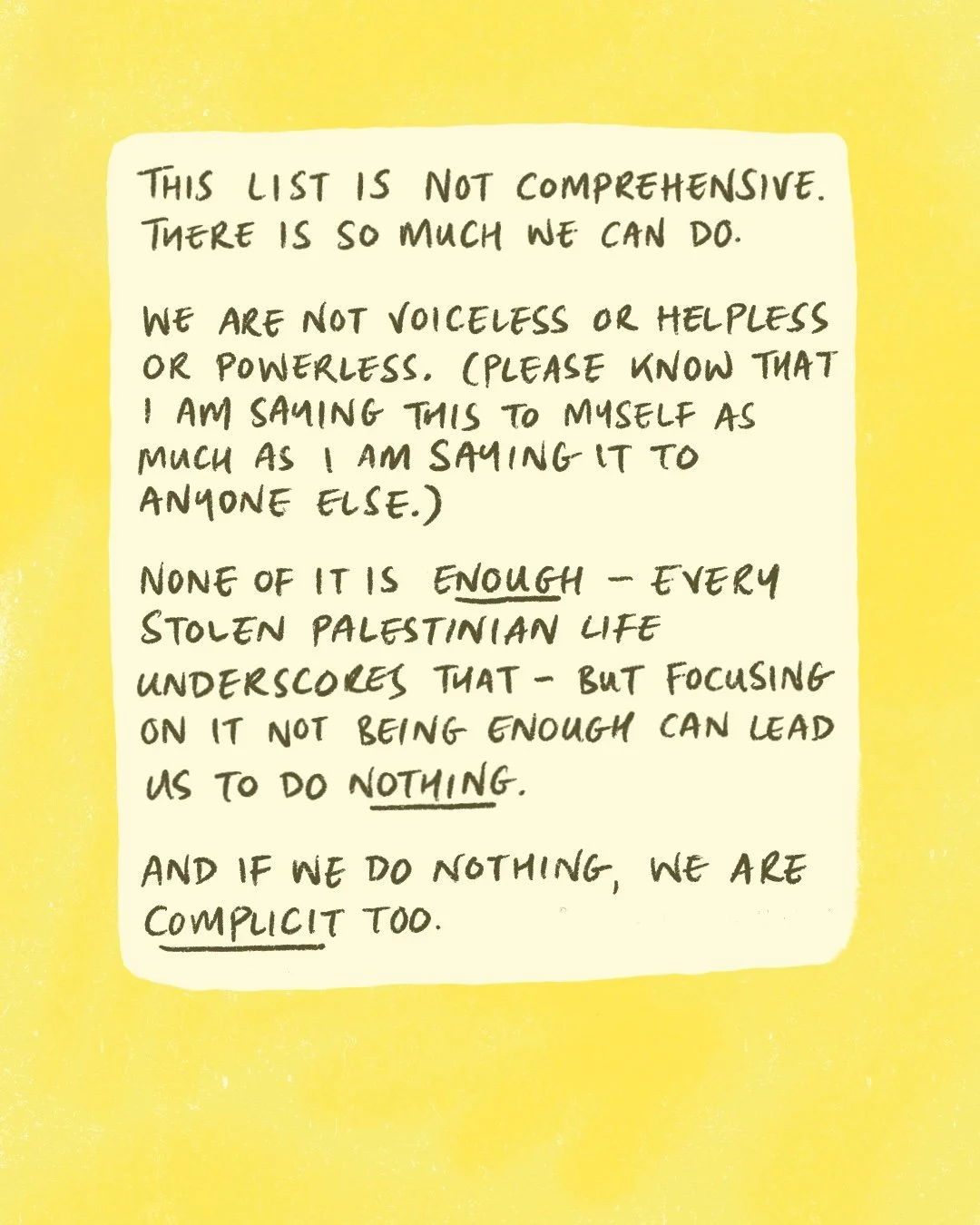

Smokies made here! Arbroath and Auchmithie Fishing Tales, summer 2024 (3/5)

1

The women did everything bloody else! Arbroath and Auchmithie Fishing Tales, summer 2024 (2/5)

1

In fishing for generations, Arbroath and Auchmithing Fishing Tales, summer 2024 (5/5)

1

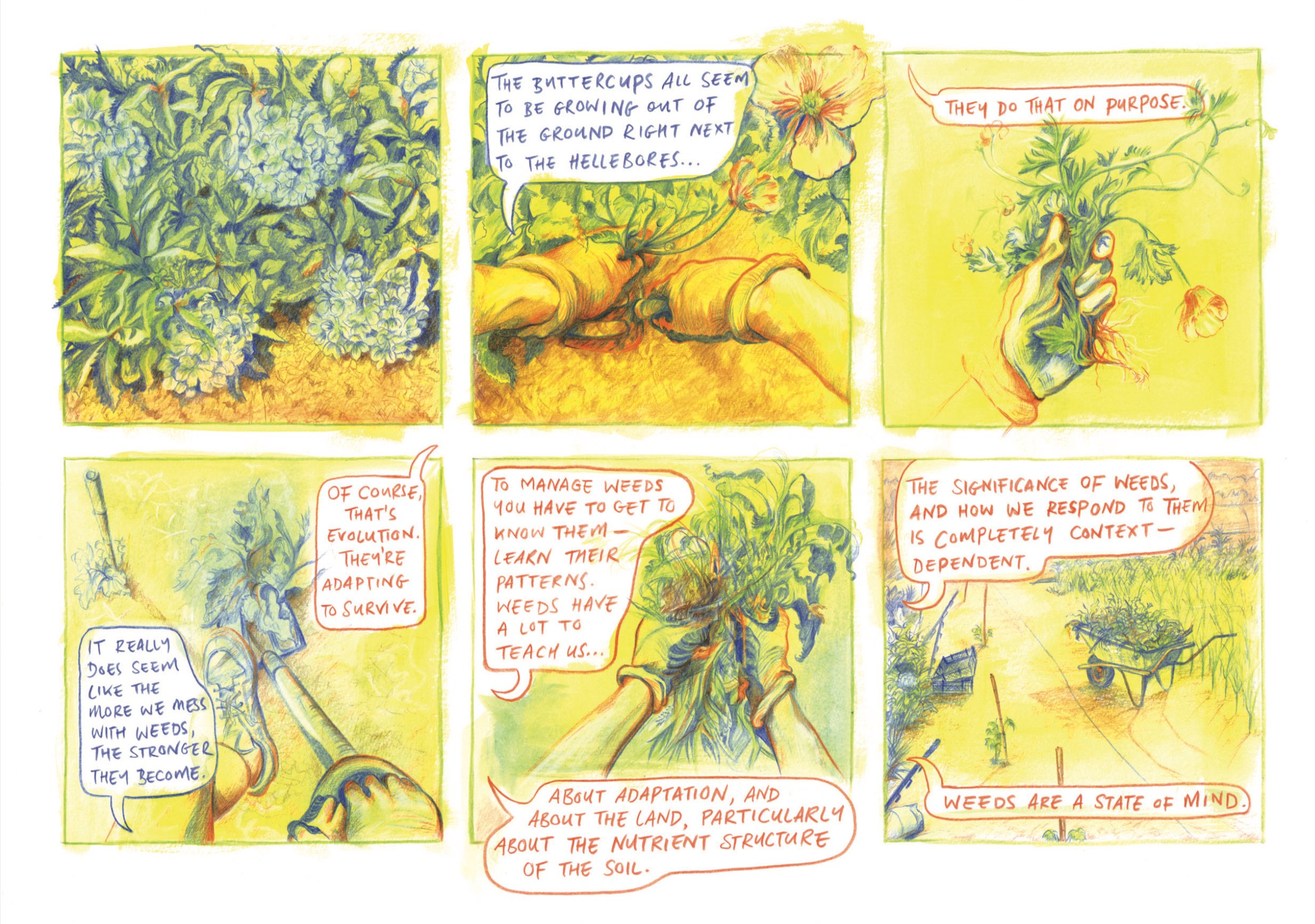

'A State of Mind' - Loveland's Weeds, summer 2023 (1/3)

1

'The Prevailing Wind' - Loveland's Weeds, summer 2023 (2/3)

1

'Super Food or Super Weed?' - Loveland's Weeds, summer 2023 (3/3)

4

Portraits - Loveland’s Weeds

3

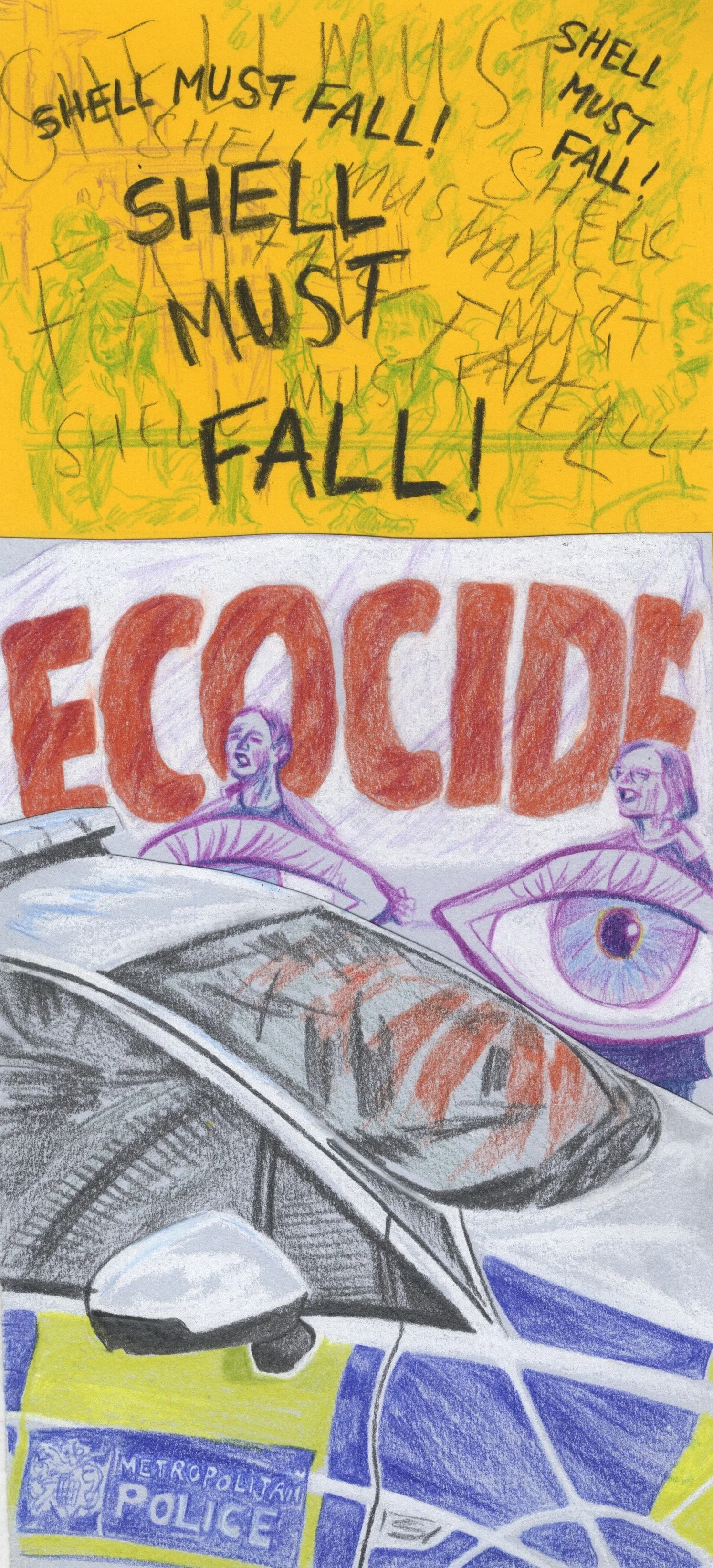

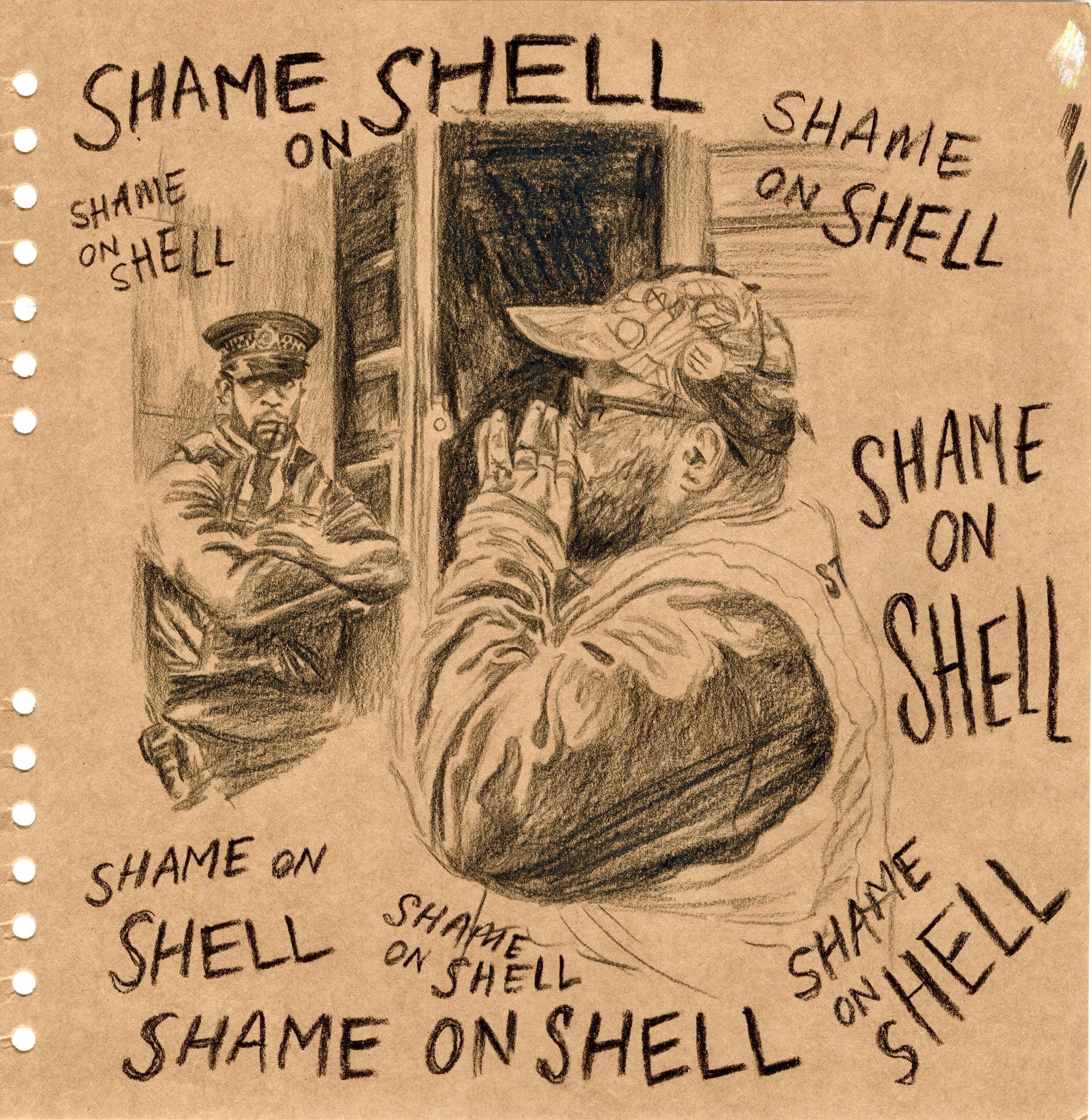

Reportage - a protest outside Shell's AGM, May 2022

4

'The violent, hopeful world of children who smuggle people' - Beyond Trafficking and Slavery

4

Cover - openDemocracy's Annual Report, 2021-22

2

Cover - Byline Times, June 2021

3

'The People's Democracy of Johnsonia' - Byline Times, May 2021

6

Beyond Trafficking and Slavery philanthrocapitalism debate, January 2021

3

Zoom portraits - spring 2021